The Silent Tower and The Silicon Mage are the first two books in Barbara Hambly’s portal fantasy series The Windrose Chronicles. For those unfamiliar with the term, a portal fantasy involves travel between two realms: our familiar Earth at some point in history and somewhere else, either Faerie, Heaven, Hell, a dreamscape, or another planet entirely. In this series, the two realms are Los Angeles in the 80s and the Empire of Ferryth on another world. In the first two books, it’s never explicitly stated whether the Empire’s planet is another Earth existing in a parallel dimension or a different planet orbiting a different sun altogether; however, both worlds contain human beings that are sufficiently similar for the same magic spells to work on both. What we are told is that our Earth, the Empire’s planet, and stranger worlds filled with utterly alien beings are all connected by the Void. The Void is only accessible by those with sufficiently advanced technology or magic. Out in the Void, there are drifting centers of power. The distance between a world and a power center determines whether or not magic exists.

So, then, we have the Empire’s planet, at the beginnings of an industrial revolution but still filled with some mages, and our Earth at the 80s, at the beginning of the computer revolution. Although mainframes, Fortran, and floppy disc drives were all in use when Hambly wrote these books, they’re now so outdated that 80s LA just seems like another secondary world, one which I’m more familiar with through old movies and clunky CGI than my own experience. As LP Hartley wrote, “the past is a foreign country.”

It’s interesting to compare the worldbuilding of 80s LA and the Empire of Ferryth. They both feel solid. In this portal fantasy, we’re given a POV from each side and, interestingly, we start in the Empire, with Caris. Although at first it seems that we begin at a generic magic school, where Caris has already graduated as a warrior guard to mages, it becomes clear early on that this world is modeled on a very specific point in history, when factories and programmable looms begin to appear in the cities but the majority of the population are still struggling farmers.

Economics seems like a primary inspiration for Hambly. The most vivid part of Joanna’s Los Angeles experience is her job at a defense contractor, programming missile control systems. Although there are no clouds of coal in her world, there’s the gloomy fog of a potential nuclear armageddon. In the Hambly books that I’ve read, these and Dragonsbane, her protagonists are not the typical fantasy women. They’re average or homely rather than beautiful, middle aged rather than teenagers. Joanna is a blonde, curly haired, shy women who’s more comfortable programming systems at 4am than talking to people, constantly staving off the advances of her seemingly oafish boyfriend Gary. It was very easy for me to identify with her and hope for her to succeed because her job is similar to my day job.

I thoroughly enjoy when Joanna applies her programming expertise to magic, breaking down problems into smaller and smaller, and easier to solve, subroutines. But this isn’t the type of magic that you get in a Brandon Sanderson novel. There’s no unified theory of magic for Joanna to discover, just the Dark Mage to trap and Abominations to destroy. I enjoy the clever construction of Sanderson’s magical systems but sometimes I just want to be awed by mysterious beings who can summon lightning from unknown dimensions.

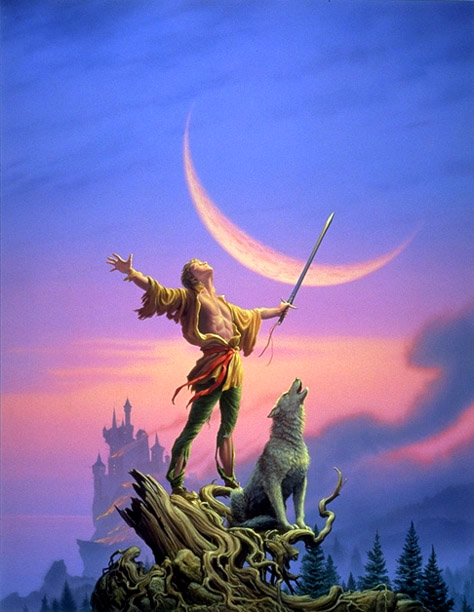

Caris, who you might at first be fooled into thinking is the hero and love interest, is a young, lithe warrior with a perfectly proportioned face who has trouble thinking for himself and craves the clarity of rules from obvious authority figures. In these first two novels, which form one complete story, Caris is cast adrift with Joanna and the wry, mad mage Antryg Windrose. Antryg is an amazingly crafted character. Throughout The Silent Tower, I was never sure of his intentions, but he charmed me as easily as he charms Caris and Joanna.

The kernel of these novels is the relationship between Joanna and Antryg. When I was in high school I got excited about the romantic relationships in books like the Wheel of Time, where horny teenagers fall for each other at their first meeting because they’re fated to but don’t have the healthiest of relationships. Now that I’m older and married, I prefer Hambly’s depiction of a relationship focused on partnership and mutual respect on top of attraction. Joanna and Antryg do have to work out their trust and communication issues, but what relationship is ideal?

There’s one unfortunate aspect of these books that prevents me from whole-heartedly recommending them. There’s one gay character who falls into the trope of decadent, depraved homosexual. Although Joanna sees his good qualities, she still refers to him as a “pervert.” This isn’t central to the book but I can’t blame anyone for finding this an insurmountable obstacle.

I’m going to leave y’all with one of my favorite moments. It’s a great example of Hambly’s all-too-realistic focus on economics but is a bit spoilery. In The Silicon Mage, Antryg and Joanna encounter a much hyped-up evil, an intelligent Abomination from another dimension. When they encounter the demon in its gorey lair, they discover that it’s not some fearsome hellspawn intent on devouring souls, but a low-level office worker who’s trapped in a world he doesn’t understand, trying to communicate the only way he can: through a body composed of human corpses. Even more humorously, he’s an technician like Joanna; only instead of computer systems, he works with xchi particles.