In the past two months I finished Tad Williams’ Shadowmarch epic fantasy tetralogy and then burned through his other, earlier epic fantasy tetralogy, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn for the third or fourth time.

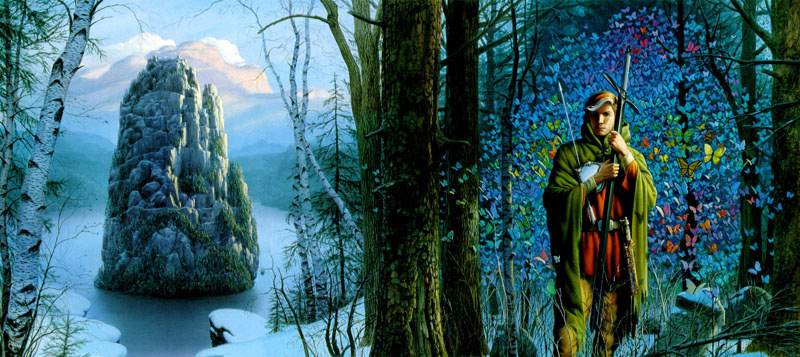

Michael Whelan’s cover for Stone of Farewell, book two of Tad Williams’ Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn fantasy series

What I dig about Williams, besides his excellent (albiet sometimes slow-paced) prose and efforts to re-upholster standard fantasy tropes, is his attempts to depict truly inhuman beings and cultures in his stories. Science fiction and fantasy authors have always grappled with these kinds of depictions. Some question if it’s even possible for us human beings, with our mental biases, to truly imagine the thoughts and cultures of some other type of intelligence. In this blog post, I’m going to discuss several attempts, how they succeed or fail, and how this relates to my own artistic practice. Be warned, this essay is long.

For his earlier epic fantasy series Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn (well worth a read if you enjoy Tolkien), Williams created the Sithi. Although sometimes they just seem non-Western rather than truly not human (atonal music, bright clothing, clicking sounds as language), sometimes, in their immortality, differently jointed bodies, or battle tactics, Williams gives us a glimpse of otherworldly beings. However, because a major part of the plot is (spoiler alert) the main characters’ increasing interaction with and understanding of the Sithi, we really see them more for the qualities that make them more like humans than their qualities that make them inhuman. Also, although it’s easy for Williams to tell us that the Sithi’s bodies and faces move as though they have different points of articulation than we do, it isn’t very easy for me to see that in my head.

The Qar, which are featured in William’s recently finished series Shadowmarch, are less human overall than the Sithi. This is because they are a physically varied group of sentient beings and we only interact with a few of the more human-looking ones. In addition, (spoiler alert) Williams brings in another group of beings even further removed from humanity, the gods. This serves to both make the Qar seem more human and forces us to contemplate the thoughts and motivations of beings infinitely more powerful than us.

I could pick and critique innumerable other examples from sci fi and fantasy, but I might as well go straight to the well, to the deepest thinker in speculative fiction: Stanislaw Lem.

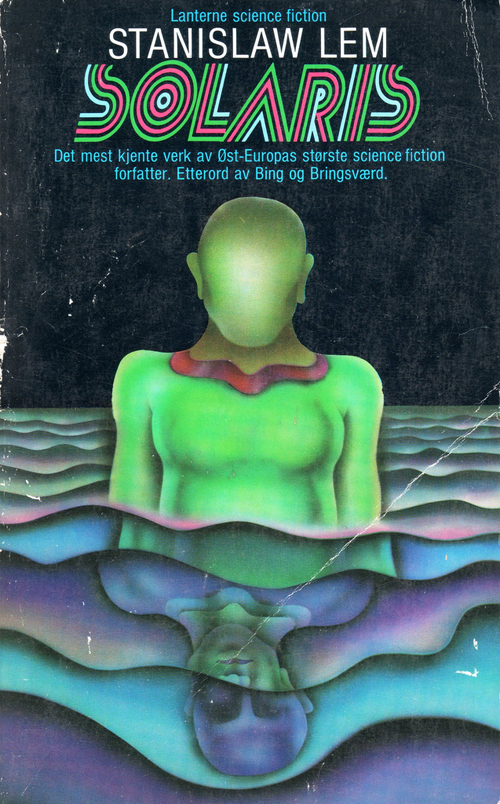

Peter Haars’ cover for Solaris by Stanislaw Lem. Via gojira2012’s flickr.

A major theme of Lem’s work is our inability to understand (and therefore communicate with) the inhuman. The plots of novels such as Solaris, His Master’s Voice, and Fiasco center on attempts by humans to communicate with aliens, with often tragic consequences.

In Solaris, for example, the titular planet is enveloped by a sentient ocean. As the human researchers try to study the ocean, the ocean studies them in turn. The ocean manifests human simulacra of people from their more powerful (often shameful) memories. The scientists try to study these simulacra but in the end they learn nothing about the planet. This story is a painful clear look at guilt and human nature. It is also a vivid portrayal of something truly alien. Lem succeeds where so many other authors fall short by never giving us any hint of the ocean’s motives or thoughts, or if it even has thoughts; in fact, it’s not even clear by the end whether the ocean truly is sentient, or if it’s just mindlessly reacting. This echoes what the scientists within the novel are able to achieve. There is a vast body of knowledge called Solaristics that names and catalogues the various phenomena that occur around and within the ocean, but no deeper understanding. In my mind, any future encounter that humanity has with aliens is much more likely to be like Solaris than like any sort of meetings of minds, like we have between the humans and Sithi in Tad Williams’ novels.

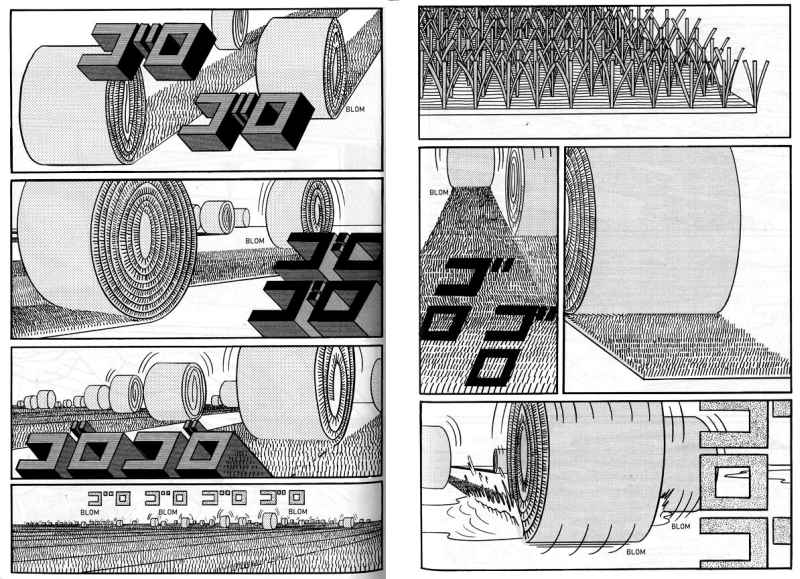

Let’s move on to attempts to represent the inhuman in comics. Comics and other narrative visual media can offer unique depictions of the inhuman. Instead of trying to describe the inhuman with language, drawings can just show it. There is no need to try and represent the dialogue or thoughts of the inhuman – just watch it act. The cartoonist Yuichi Yokoyama crafts narratives of the inhuman that are just as powerful as Lem’s, but from an opposite perspective. Yokoyama takes narratives involving human actors and strips them of any interior thought. In his collecton of shorter works New Engineering, Yokoyama depicts humans battling or building, but because he focuses strictly on the actions that happen, the humans become incomprehensible actors who battle or build for unknowable ends.

A Yuichi Yokoyama spread from New Engineering, via La Cárcel de Papel. Read right to left. In the English book, they have translations of the sound effects. Apparently they mean “sound of astroturf rolling.”

In an interview that is published in New Engineering (that I saw quoted in this excellent blog post by Tom Kaczynski where he compares Yokoyama to Ballard), Yokoyama states that creating “characters without psychology” is his goal: “I am interested neither in the feelings of people nor in their emotions. I examine only what is to the eye.”

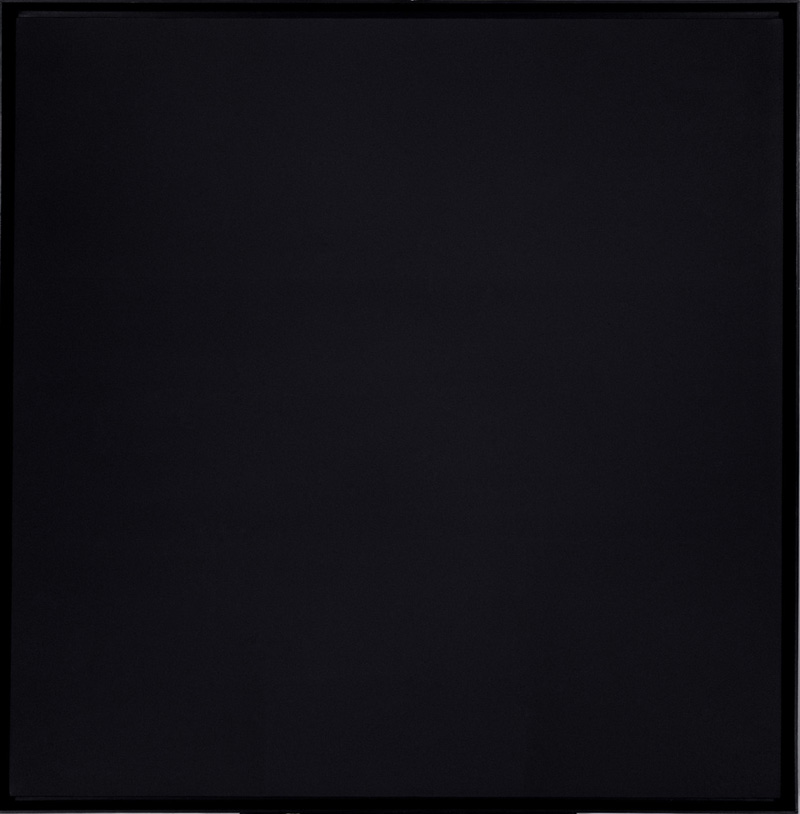

One way to look at Yokoyama’s comics to see them as very formal. Yokoyama isn’t interested in narrative, he’s just interested in movement and action. This ties him into the modernist project of abstraction. In a way, abstract art that is only concerned with color and form can be seen as an attempt to represent the inhuman. Although some abstract painters, such as Mark Rothko, were concerned with representing their interior feelings, others, such as Ad Reinhardt, just wanted to show the reality of paint.

Abstract Painting by Ad Reinhardt, 60 x 60 inches, 1960-66, via the hic svnt leones tumblr.

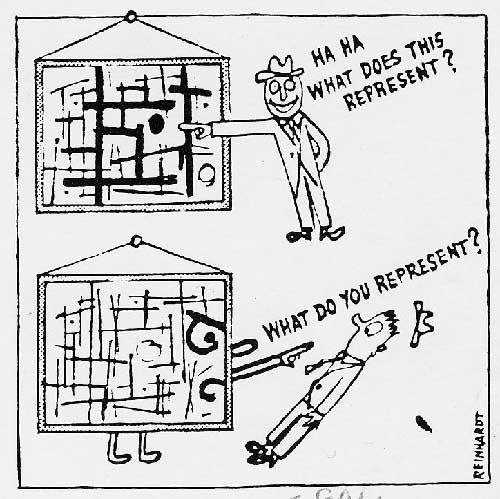

This cartoon by Ad Reinhardt really sums it all up. Painting becomes its own thing with it’s own interiority inaccessible to humans.

Ad Reinhardt cartoon via katiek2’s flickr.

I’m fascinated by these various attempts to understand and connect with something outside of humanity. As human beings, we are limited by our minds and bodies, and the biases that come with them. I know that it’s a doomed quest, but I want to try to go beyond being human, at least through my art, to depict a clear, unclouded vision of the cosmos. Or maybe it’s the vision of a vast, eldritch horror that has been drifting in the cold, dark spaces between galaxies for millenia. Either way, it allows me to stretch, ever so briefly, to the limits of my thought.